Kenya is headed for its fourth presidential succession since independence in four month’s time. In this four-part series, Kwendo Opanga analyses the politics of the transfer of power.

Nairobi

The political tyro of President Daniel arap Moi’s failed succession project of 2002 has matured into 2022’s manipulator and choreographer of his own presidential succession. Unexpectedly, Moi was desperate to hand over the reins of power to his handpicked, untried and untested 41-year-old Uhuru Kenyatta.

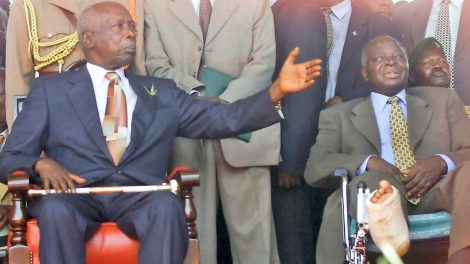

Daniel Moi (l), Mwai Kibaki (c) and Uhuru KenyattaBut, as the presidential election campaign drew to a close, he knew that would not happen. It would be to Mwai Kibaki, his former Vice-President of nine years, whom he dropped like a hot brick in 1988, that he would hand over the sword of office. Kibaki – since deceased – was coasting to a landslide victory.

Kenyatta’s pregnant silence and Njonjo's ominous threat scattered the group, scuppered their scheme and paved the way for the constitution-prescribed process to the imminent succession.

As the votes were counted and as the results were announced, Moi summoned Home Affairs Minister William Ruto, who was in State House, Nairobi, to his office.

President Uhuru KenyattaHe instructed the 36-year-old to urgently find Kenyatta and together prepare and deliver a concession speech.

With 71-year-old Kibaki as President and Kenyatta as Leader of the Official Opposition, Moi appeared resigned to transition from President Moi to citizen Moi. He had not felt the same way in 1992 or 1997.

Then, many opposition figures, believing Moi and KANU would lose, loudly threatened to haul him to court to face misuse and abuse of office charges when they took over.

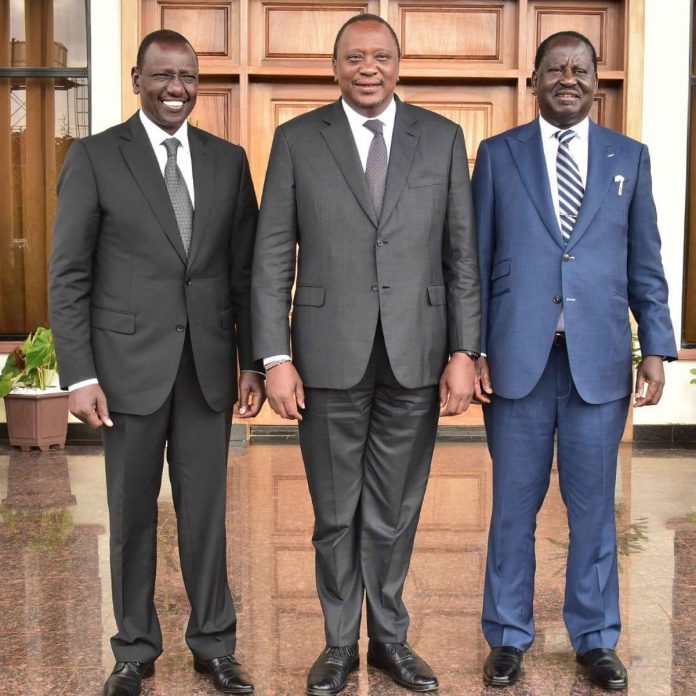

President Uhuru Kenyatta (l), Raila Odinga (c) and DP William RutoHow a president regards his succession reveals his fears, hopes and designs about losing power and the incoming dispensation.

It also draws attention to the political and legal mechanisms through which a presidential succession is viewed by the interested parties in the political arena.

ODM leader Raila OdingaBut it is not only the president who is concerned about his imminent exit.

Family, friends and relatives, allies and functionaries in party, government and industry, will similarly be interested, and may seek to influence the succession.

That brings into focus the constitution vis-a-vis the scheming for power of the political elites and the president who is in the eye of the storm.

Rewind to 1976. The failed change-the-constitution drive presented an invitation to founding President Jomo Kenyatta, then 79, to get involved in, if not altogether personally manage, his succession.

Put another way, allies goaded the President to reject and replace Moi before he left office. In 1978 old Jomo died and his VP of 12 years succeeded him in a peaceful transfer of power.

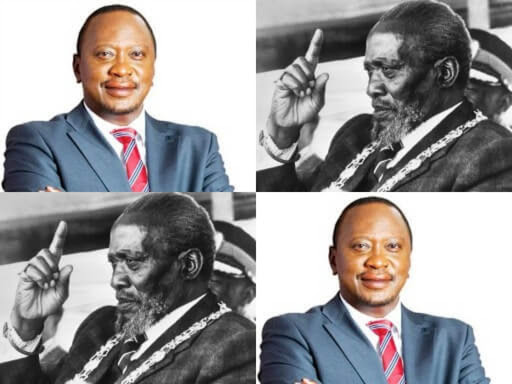

Mzee Jomo Kenyatta and his son, UhuruThe target of the change-the-constitution group was Moi. Standing in its way was the constitution.

So the group wanted the basic law amended so that a sitting V-P could not automatically inherit the top job should it fall vacant by reason of death or incapacitation of the incumbent.

The plotters did not want Moi – since deceased – to become president because he was not from their tribe of choice.

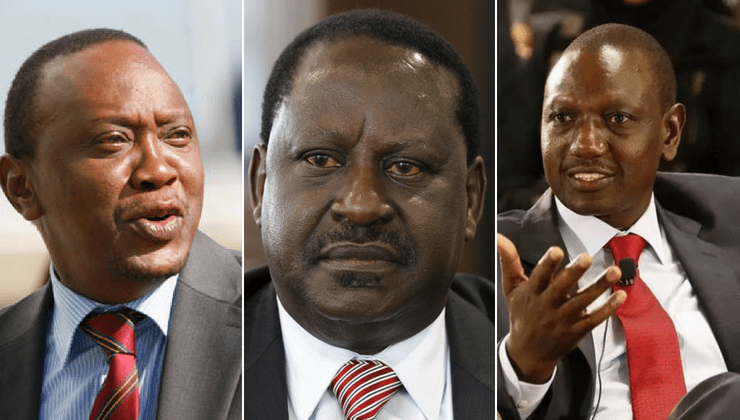

Mwai Kibaki (l), Daniel Moi (c) and Raila Odinga (r)The task facing the founding President was simple; show his hand by publicly endorsing Moi and therefore end the campaign, or thereby challenge the campaigners to defy him, or do their bidding.

Uncharacteristically, Kenyatta, who was said to whip ministers and politicians who rubbed him up the wrong way, chose to keep quiet, but not so his power-playing Attorney-General Charles Njonjo.

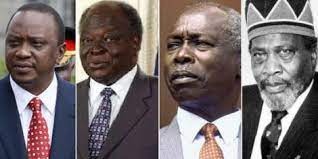

Uhuru,Kibaki,Moi and Mzee KenyattaNjonjo – since deceased – threatened the group whose ring leaders included Njenga Karume, the Kiambu tycoon and chairman of the powerful Gikuyu Embu Meru Association; Njoroge Mungai, a former foreign minister and Kenyatta’s personal physician; Paul Ngei, a Cabinet Minister and member of the fabled Kapenguria Six freedom heroes; and Kihika Kimani, founder of the giant Nakuru-based Ngwataniro land buying company.

He told them – all since deceased – it was a treasonable offence to think, imagine or otherwise encompass the death of the President.

Kenyatta died in office. Moi and Kibaki retired from office, the latter in 2013. Kenyatta and Kibaki let the law dictate their successions. Moi sought to manipulate the process and succeed himself through Kenyatta’s son.

Kenyatta’s pregnant silence and Njonjo’s ominous threat scattered the group, scuppered their scheme and paved the way for the constitution-prescribed process to the imminent succession.

However, the writing was on the wall. One, if the rich and powerful were going to have their way, there were going to be fights over future presidential successions and the constitution would be a casualty.

Two, Kenyatta resisted his political Mafia, but there was no guarantee that those coming after him would defer to the constitution.

Moi and Kibaki in 2002Indeed, it has since been argued that Kenyatta had a secret succession pact with Moi which bound the latter to protect the former’s family and vast commercial interests.

Three, future presidential successions were going to be action-packed and or volatile affairs. Presidential polls were similarly going to be heated and would exert pressure on the players, electorate and umpires.

Kenyatta died in office. Moi and Kibaki retired from office, the latter in 2013. Kenyatta and Kibaki let the law dictate their successions. Moi sought to manipulate the process and succeed himself through Kenyatta’s son.

End